| Section C: Risks and benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy |

Select excerpts from audio segment 2 Select excerpts from audio segment 2

DR LOVE: How do you explain to patients how adjuvant therapy affects

the risk of relapse? For example, you mentioned that without treatment,

patients with Stage III tumors have about a 50-50 chance of the tumor

coming back. How does chemotherapy affect those odds? DR LOVE: How do you explain to patients how adjuvant therapy affects

the risk of relapse? For example, you mentioned that without treatment,

patients with Stage III tumors have about a 50-50 chance of the tumor

coming back. How does chemotherapy affect those odds? |

DR MARSHALL: Let’s begin by focusing on the traditional chemotherapy,

5-FU. The best way to think of this is that you’re in a group of 100 patients

that have the same cancer as you do. Now, 50 of those 100 patients could

not benefit from chemotherapy because they don’t have residual cancer. The

surgeon did get it all, and no seeds are taking root. That leaves 50 patients of

the 100 that we started with who have seeds. Now, frankly, in all of those 50

patients, if left alone, eventually those seeds would grow and eventually the

cancer would kill them. DR MARSHALL: Let’s begin by focusing on the traditional chemotherapy,

5-FU. The best way to think of this is that you’re in a group of 100 patients

that have the same cancer as you do. Now, 50 of those 100 patients could

not benefit from chemotherapy because they don’t have residual cancer. The

surgeon did get it all, and no seeds are taking root. That leaves 50 patients of

the 100 that we started with who have seeds. Now, frankly, in all of those 50

patients, if left alone, eventually those seeds would grow and eventually the

cancer would kill them.

We’ve known for about 20 years that if you give chemotherapy to this group

— and here, we’re really talking about the 50 patients that have seeds — 20

of those patients will now not grow seeds. We’ll cure those 20 with chemotherapy.

So, the odds go from 50-50 to more like 70-30. Our real shortfall

is that we can’t figure out who’s in the good 50 and who’s in the bad 50.

They look alike to us. We can’t tell. We don’t have tests yet that distinguish

the group that should be getting chemotherapy from those who don’t need it

because they’re already cured.

The other point I want to make is that even with the chemotherapy, in a fair

number of patients — in this example, as many as 30 of the 100, altogether —

the cancer will come back anyway. And it’s that group of patients with which

our new medicines have begun to whittle away the numbers, and that 30 is

getting smaller as we cure more of those patients with the newer medicines.

DR LOVE: So to follow that out in terms of the Stage III patients, essentially,

you would say to a patient, “If there were 100 patients like you, about a fifth

of the total, or about 20 people, by receiving the treatment, will go from

eventually developing an incurable situation to being cured.” DR LOVE: So to follow that out in terms of the Stage III patients, essentially,

you would say to a patient, “If there were 100 patients like you, about a fifth

of the total, or about 20 people, by receiving the treatment, will go from

eventually developing an incurable situation to being cured.”

DR MARSHALL: That’s right. And I also tell patients that they themselves may

never know if they benefited from the chemotherapy. If their cancer never

comes back, they won’t know whether they were in the good 50 or they were

in the group that actually got the last few seeds knocked off by the chemotherapy.

By the same token, if their cancer does come back, they won’t know

whether the chemotherapy may have delayed the time for it to come back or

whether it may have killed some but not all of the cancer cells. So it’s very hard

for patients themselves to understand if they’re benefiting from the treatment. DR MARSHALL: That’s right. And I also tell patients that they themselves may

never know if they benefited from the chemotherapy. If their cancer never

comes back, they won’t know whether they were in the good 50 or they were

in the group that actually got the last few seeds knocked off by the chemotherapy.

By the same token, if their cancer does come back, they won’t know

whether the chemotherapy may have delayed the time for it to come back or

whether it may have killed some but not all of the cancer cells. So it’s very hard

for patients themselves to understand if they’re benefiting from the treatment.

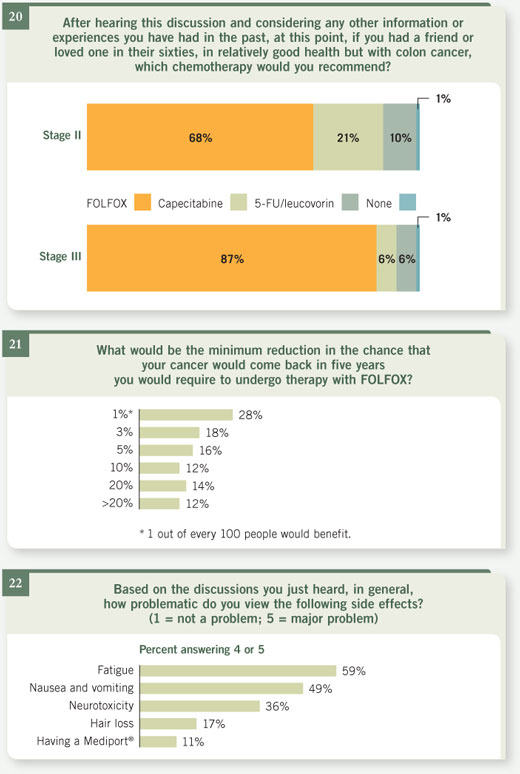

DR LOVE: Now, again focusing on patients with Stage III disease, how is the

risk of relapse affected when you utilize the newer approach that has come

into practice the last few years, the regimen of FOLFOX, with 5-FU and

oxaliplatin, or Eloxatin®, compared to 5-FU? DR LOVE: Now, again focusing on patients with Stage III disease, how is the

risk of relapse affected when you utilize the newer approach that has come

into practice the last few years, the regimen of FOLFOX, with 5-FU and

oxaliplatin, or Eloxatin®, compared to 5-FU?

DR MARSHALL: The numbers get better. We probably pick up about an

additional five percent chance of remaining relapse free, maybe a little bit

higher. To put some hard numbers to it, in the actual major study that has

been reported — the MOSAIC trial — of the patients who only received

5-FU, about 65 percent remained free of relapse. But when the oxaliplatin

was added, the number went to 72 percent. DR MARSHALL: The numbers get better. We probably pick up about an

additional five percent chance of remaining relapse free, maybe a little bit

higher. To put some hard numbers to it, in the actual major study that has

been reported — the MOSAIC trial — of the patients who only received

5-FU, about 65 percent remained free of relapse. But when the oxaliplatin

was added, the number went to 72 percent.

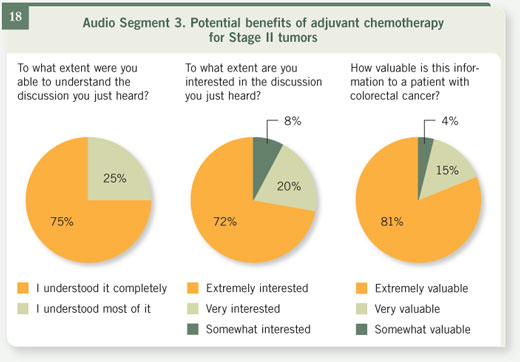

Select excerpts from audio segment 3 Select excerpts from audio segment 3

DR LOVE: How do you discuss the numbers with the patients who have

lower-risk tumors or Stage II colon cancer? DR LOVE: How do you discuss the numbers with the patients who have

lower-risk tumors or Stage II colon cancer? |

DR MARSHALL: With Stage II disease, of course, you start off with slightly

better odds. There, your numbers are roughly 75-25, so the potential benefit

isn’t as much. And in fact, when one looks at the data that we have for this

group of patients, the best guess we have is that overall, with the older 5-FU

regimens, about three out of 100 will be cured as a result of treatment, which

means that we have to treat 100 patients to cure three who would otherwise

have a recurrence. DR MARSHALL: With Stage II disease, of course, you start off with slightly

better odds. There, your numbers are roughly 75-25, so the potential benefit

isn’t as much. And in fact, when one looks at the data that we have for this

group of patients, the best guess we have is that overall, with the older 5-FU

regimens, about three out of 100 will be cured as a result of treatment, which

means that we have to treat 100 patients to cure three who would otherwise

have a recurrence.

DR LOVE: What are the numbers with FOLFOX? DR LOVE: What are the numbers with FOLFOX?

DR MARSHALL: Of patients in the MOSAIC trial with Stage II disease who

received FOLFOX, a surprising 87 percent were without relapse, which was

about three percent higher than in the 5-FU group. DR MARSHALL: Of patients in the MOSAIC trial with Stage II disease who

received FOLFOX, a surprising 87 percent were without relapse, which was

about three percent higher than in the 5-FU group.

DR LOVE: How do you see patients reacting to those numbers? DR LOVE: How do you see patients reacting to those numbers?

DR MARSHALL: It’s very interesting to see that different patients will make

different decisions based on that information. Some will say, “Shoot. If it’s

one percent, I’ll do it.” Others will say, “Three percent is not enough for me

to risk it.” And when it comes down to the final decision, the key is the side

effects of therapy. DR MARSHALL: It’s very interesting to see that different patients will make

different decisions based on that information. Some will say, “Shoot. If it’s

one percent, I’ll do it.” Others will say, “Three percent is not enough for me

to risk it.” And when it comes down to the final decision, the key is the side

effects of therapy.

If treatment were completely without side effects, I think we’d all do it. What

the heck? This is a life-and-death thing, and if you were going to improve

your chances of being alive past the next five years by a small percentage, you

probably would do it (although most of us who smoke keep smoking, so you

wonder).

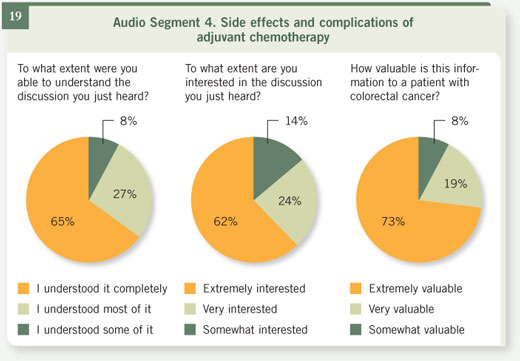

Select excerpts from audio segment 4 Select excerpts from audio segment 4

DR LOVE: What do you say to patients about the risks of adjuvant chemotherapy? DR LOVE: What do you say to patients about the risks of adjuvant chemotherapy? |

DR MARSHALL: The older therapy of giving intravenous (IV) 5-FU is

relatively easy. A patient comes to the clinic, usually one day a week, and

receives a quick injection of the 5-FU, almost always administered with

another medicine called leucovorin, which enhances the effects of 5-FU

against the cancer. DR MARSHALL: The older therapy of giving intravenous (IV) 5-FU is

relatively easy. A patient comes to the clinic, usually one day a week, and

receives a quick injection of the 5-FU, almost always administered with

another medicine called leucovorin, which enhances the effects of 5-FU

against the cancer.

But now a bunch of different recipes exist for administering 5-FU. Some

doctors administer it one day a week for several weeks in a row and then give

the patient a break. Others like to administer it five days in a row and then

give the patient several weeks off. Recently, what I think is an even better way

to administer the medicine has emerged, in which it is infused over a longer

period of time, which seems to produce fewer side effects for patients as well

as working better against the cancer.

DR LOVE: How long does the patient receive the treatment? DR LOVE: How long does the patient receive the treatment?

DR MARSHALL: The total package is about six months of treatment. DR MARSHALL: The total package is about six months of treatment.

DR LOVE: Other than the inconvenience of having the infusion done, what

kinds of side effects do patients experience? DR LOVE: Other than the inconvenience of having the infusion done, what

kinds of side effects do patients experience?

DR MARSHALL: About 15 percent of patients will lose enough hair to notice.

But the bigger side effect with this medicine is mouth sores — tenderness and

peeling in the mouth. Some diarrhea is also seen with 5-FU. The blood counts

can go down a bit, and fatigue is commonly seen. But all in all, it’s pretty

well tolerated. As I tell patients, it’s not usually “crawl-under-a-rock-and-die”

chemotherapy. It’s compatible with normal daily living. Patients usually drive

themselves in their cars to receive this chemotherapy. And there’s not a great

deal of nausea and vomiting associated with it. So it’s relatively easy chemotherapy. DR MARSHALL: About 15 percent of patients will lose enough hair to notice.

But the bigger side effect with this medicine is mouth sores — tenderness and

peeling in the mouth. Some diarrhea is also seen with 5-FU. The blood counts

can go down a bit, and fatigue is commonly seen. But all in all, it’s pretty

well tolerated. As I tell patients, it’s not usually “crawl-under-a-rock-and-die”

chemotherapy. It’s compatible with normal daily living. Patients usually drive

themselves in their cars to receive this chemotherapy. And there’s not a great

deal of nausea and vomiting associated with it. So it’s relatively easy chemotherapy.

DR LOVE: What about capecitabine? DR LOVE: What about capecitabine?

DR MARSHALL: Capecitabine, or Xeloda, is a wonderful invention. For 40

years we’ve been playing with 5-FU as an intravenous therapy, and finally,

about a decade ago, an oral version of this medicine was developed. And as

we’ve said, the best way to administer 5-FU does appear to be a prolonged

exposure, spreading it out instead of administering it all at once. An oral

medicine allows us to do that without having to use a port for the IV and

a pump. DR MARSHALL: Capecitabine, or Xeloda, is a wonderful invention. For 40

years we’ve been playing with 5-FU as an intravenous therapy, and finally,

about a decade ago, an oral version of this medicine was developed. And as

we’ve said, the best way to administer 5-FU does appear to be a prolonged

exposure, spreading it out instead of administering it all at once. An oral

medicine allows us to do that without having to use a port for the IV and

a pump.

A recent study now allows us to bring the oral 5-FU or capecitabine into use

for patients with Stage II and Stage III disease. In this study, half the patients

received the old IV 5-FU, five days in a row and then a month off to recover,

and the other half received capecitabine two weeks in a row, having one week

off. And we’re very pleased to report that the group who received the oral

medicine did better. They had slightly fewer cancer relapses and, most significantly,

a better side-effect profile. So the oral medication won in the two most

important areas, how well it works and how safe it is.

And so capecitabine has become a very popular option for patients with

Stage II and Stage III disease after surgery. It prevents the need for coming in

regularly for IV infusions. The medicine has side effects but is relatively well

tolerated. Patients don’t lose their hair, and nausea is not a big issue.

DR LOVE: Let’s talk about some of the newer forms of adjuvant therapy that

you are now offering to your patients in this situation. DR LOVE: Let’s talk about some of the newer forms of adjuvant therapy that

you are now offering to your patients in this situation.

DR MARSHALL: The most exciting new research comes from a study that

added the medicine oxaliplatin, or Eloxatin, to 5-FU. This recipe of giving

oxaliplatin and 5-FU together is known as FOLFOX. It’s a little trickier, a

little bit more intensive, if you will, than the old 5-FU/leucovorin regimens

that we just talked about or capecitabine. This recipe requires that patients

receive an IV infusion for two days. So they come to the clinic and receive

about two to three hours’ worth of intravenous treatment in the clinic, but

then they go home with a small battery-powered pump. It’s about the size of a

traditional Walkman, and they carry this pump for two days. DR MARSHALL: The most exciting new research comes from a study that

added the medicine oxaliplatin, or Eloxatin, to 5-FU. This recipe of giving

oxaliplatin and 5-FU together is known as FOLFOX. It’s a little trickier, a

little bit more intensive, if you will, than the old 5-FU/leucovorin regimens

that we just talked about or capecitabine. This recipe requires that patients

receive an IV infusion for two days. So they come to the clinic and receive

about two to three hours’ worth of intravenous treatment in the clinic, but

then they go home with a small battery-powered pump. It’s about the size of a

traditional Walkman, and they carry this pump for two days.

At the end of the two days, typically patients come back to the clinic and have

the pump disconnected. As I describe it to patients, you’re two days on, 12

days off. And that pattern repeats for 12 cycles, or, in essence, six months.

DR LOVE: What do you tell patients to expect in terms of side effects or

effects on their quality of life by adding oxaliplatin? DR LOVE: What do you tell patients to expect in terms of side effects or

effects on their quality of life by adding oxaliplatin?

DR MARSHALL: Oxaliplatin has, as its major side effect, a nerve toxicity,

which comes in two f lavors. One happens on the day you receive the treatment.

On that night, when you go home and go into the refrigerator or go

into the freezer and touch something cold or drink something cold, you

possibly experience an unpleasant feeling in the fingertips and in the throat. DR MARSHALL: Oxaliplatin has, as its major side effect, a nerve toxicity,

which comes in two f lavors. One happens on the day you receive the treatment.

On that night, when you go home and go into the refrigerator or go

into the freezer and touch something cold or drink something cold, you

possibly experience an unpleasant feeling in the fingertips and in the throat.

Also, if you’re one who likes to walk around barefoot on a cold kitchen f loor,

you might notice it in your toes as well. It’s really not that big of a deal,

medically, but it’s a nuisance for patients. It lasts about two to three, up to five

to seven days with each cycle. You learn to tolerate it. You drink your beer

warm, if you will.

But the other f lavor of nerve toxicity, the cumulative nerve toxicity, is a

pins-and-needles feeling in the fingertips and in the toes that almost everybody

gets if they keep receiving oxaliplatin for 12 cycles, or six months. I also

describe it to patients as feeling as if these parts of their body are asleep. And

some patients will get this fairly badly, to the point where they have trouble

buttoning buttons, tying shoes, writing checks, that sort of thing. So that’s

something that both the patient and an oncologist have to keep in mind and

keep as a very open dialogue as this chemotherapy goes along.

Fortunately, that nerve toxicity, even though it’s pretty common, reverses in

essentially everybody by about a year to a year and a half after the end of the

treatment. So it’s not a permanent nerve toxicity, but it is something we want

to watch out for and try and prevent, if we can.

DR LOVE: Overall, in what fraction of patients is the nerve toxicity enough

that it interferes with their quality of life? DR LOVE: Overall, in what fraction of patients is the nerve toxicity enough

that it interferes with their quality of life?

DR MARSHALL: It’s rare for it to get that bad. In the MOSAIC study, only

12 percent of patients experienced that degree of nerve toxicity. And frankly,

most of us have adapted our behavior recently, so that when patients come in

with more severe complaints — which might be at cycle 10, 11, or 12, really

the last month of the chemotherapy — we might back off on the oxaliplatin

and not give as much, or even hold it altogether, to avoid that toxicity from

getting any worse. So, as we’ve gotten smarter about the side effects, we’re

better able to keep patients out of that trouble. DR MARSHALL: It’s rare for it to get that bad. In the MOSAIC study, only

12 percent of patients experienced that degree of nerve toxicity. And frankly,

most of us have adapted our behavior recently, so that when patients come in

with more severe complaints — which might be at cycle 10, 11, or 12, really

the last month of the chemotherapy — we might back off on the oxaliplatin

and not give as much, or even hold it altogether, to avoid that toxicity from

getting any worse. So, as we’ve gotten smarter about the side effects, we’re

better able to keep patients out of that trouble.

DR LOVE: What about the more global effects on people’s quality of life:

nausea, vomiting, hair loss, feeling tired? What’s the difference between 5-FU

or capecitabine and FOLFOX? DR LOVE: What about the more global effects on people’s quality of life:

nausea, vomiting, hair loss, feeling tired? What’s the difference between 5-FU

or capecitabine and FOLFOX?

DR MARSHALL: Some differences do exist. We talked about the nerve

toxicity. Hair loss is not a big issue with oxaliplatin versus 5-FU. We do use nausea medicines to prevent nausea, and because we’re so good at that now, it

is rare that patients experience nausea and vomiting with this treatment. DR MARSHALL: Some differences do exist. We talked about the nerve

toxicity. Hair loss is not a big issue with oxaliplatin versus 5-FU. We do use nausea medicines to prevent nausea, and because we’re so good at that now, it

is rare that patients experience nausea and vomiting with this treatment.

Oxaliplatin is a little bit harder on the bone marrow than 5-FU, so patients

will more commonly have low platelet counts or low white blood cell counts.

But again, we’re pretty good at managing that and adjusting around it. Patients

can also develop low red blood cell counts, and when patients are anemic, they

of course get tired. And we do have new medicines that will help with the

fatigue and keep it from getting too bad.

But notably, the phenomenon that I’ve noticed is that because we’re so much

better at chemotherapy treatments and because patients are tolerating chemotherapy

better and living fairly normal lives, we are wearing them out.

Probably the most common symptom that patients complain of with each cycle

is a day or two of sit-around-the-couch fatigue — not hit-the-bed-and-can’t-get-

up fatigue but really just not feeling motivated to get up and do much. But

then, after a couple of days, they pick up pretty quickly.

So fatigue is a big element of chemotherapy. It fortunately does not seem to be

overly limiting in terms of patients going to work and driving and doing daily

activities. But in an occasional patient the fatigue is more of a major issue, so

we watch out for that as well.

DR LOVE: Listening to you, trying to put myself in the place of a patient,

what’s coming across is that the traditional 5-FU or capecitabine has a

relatively minor impact on the patient, particularly compared to some of the

other chemotherapies out there. It sounds as if adding in the oxaliplatin with

the FOLFOX regimen makes treatment a little bit more challenging, but it

doesn’t sound dramatically worse. Is that what you tell your patients? DR LOVE: Listening to you, trying to put myself in the place of a patient,

what’s coming across is that the traditional 5-FU or capecitabine has a

relatively minor impact on the patient, particularly compared to some of the

other chemotherapies out there. It sounds as if adding in the oxaliplatin with

the FOLFOX regimen makes treatment a little bit more challenging, but it

doesn’t sound dramatically worse. Is that what you tell your patients?

DR MARSHALL: That’s right. And I don’t want to underplay the side effects

that happened with the old regimen. The old 5-FU regimens often landed

people in the hospital with dehydration, either with diarrhea or with mouth

sores. The newer regimen really does not have that effect. It’s rare that we

would admit a patient because of side effects from the newer chemotherapy

regimens. So in terms of the safety of FOLFOX, we’re trading for a little bit

more hassle with the port and the pump and the nerve toxicity. DR MARSHALL: That’s right. And I don’t want to underplay the side effects

that happened with the old regimen. The old 5-FU regimens often landed

people in the hospital with dehydration, either with diarrhea or with mouth

sores. The newer regimen really does not have that effect. It’s rare that we

would admit a patient because of side effects from the newer chemotherapy

regimens. So in terms of the safety of FOLFOX, we’re trading for a little bit

more hassle with the port and the pump and the nerve toxicity.

|