You are here: Home: CCU 1 | 2006: Herbert Hurwitz, MD

Tracks 1-20 |

| Track 1 |

Introduction by Neil Love, MD |

| Track 2 |

Bevacizumab-associated

hypertension |

| Track 3 |

Clinical evaluation of risk for

bevacizumab-associated

arteriovascular events |

| Track 4 |

Potential cardiovascular effects

of bevacizumab |

| Track 5 |

Potential factors contributing to

bowel perforations in studies

of bevacizumab |

| Track 6 |

Bevacizumab-associated

bleeding complications |

| Track 7 |

Management of

bowel-related complications |

| Track 8 |

Timing of bevacizumab administration

and surgery |

| Track 9 |

Effect of bevacizumab on

hepatic regeneration |

| Track 10 |

Role of VEGF inhibition in the

adjuvant setting |

|

| Track 11 |

Potential mechanisms of action

of bevacizumab |

| Track 12 |

Clinical use of

adjuvant bevacizumab |

| Track 13 |

Administration of bevacizumab

beyond chemotherapy in the

adjuvant setting |

| Track 14 |

Clinical activity of

single-agent bevacizumab |

| Track 15 |

Continuation of bevacizumab

after disease progression |

| Track 16 |

Determining the optimal dose

of bevacizumab |

| Track 17 |

Evaluation of cetuximab and

bevacizumab in combination |

| Track 18 |

Management of bevacizumab-related

side effects |

| Track 19 |

Pharmacoeconomic evaluation

of novel therapies |

| Track 20 |

Combining capecitabine

with bevacizumab |

|

|

Select Excerpts from the Interview

Track 2 Track 2

DR LOVE: Can you summarize the current available database on the

safety of bevacizumab? DR LOVE: Can you summarize the current available database on the

safety of bevacizumab? |

DR HURWITZ: So far, the main side effect has been hypertension that, in

general, is modest and easily manageable. It occurs in about a quarter of

all patients, and perhaps one, two or three in 10 patients will need to start

receiving blood pressure medication or will need an adjustment to a component

of their blood pressure regimen. In general, all blood pressure medications used to date have been successful. The key issue is close monitoring of

the patient. DR HURWITZ: So far, the main side effect has been hypertension that, in

general, is modest and easily manageable. It occurs in about a quarter of

all patients, and perhaps one, two or three in 10 patients will need to start

receiving blood pressure medication or will need an adjustment to a component

of their blood pressure regimen. In general, all blood pressure medications used to date have been successful. The key issue is close monitoring of

the patient.

As oncologists, we used to be able to forget about many general internal

medicine issues because cancer mortality was the most important issue for our

patients. Now that patients are able to stay on treatments for a year and longer

in some cases, management of side effects will be important.

In particular, blood pressure should probably be measured at every clinic visit,

and if a clear trend toward increased blood pressure appears, medication should

be instituted. Best clinical judgment should be used in the selection and titration

of any agent.

DR LOVE: Is anything new in terms of what is known about the mechanism

of developing hypertension? DR LOVE: Is anything new in terms of what is known about the mechanism

of developing hypertension?

DR HURWITZ: The mechanism is not yet well understood. Preclinical models

and some experience in the cardiovascular literature suggest that nitric oxide-mediated

mechanisms are likely involved (Shen 1999). DR HURWITZ: The mechanism is not yet well understood. Preclinical models

and some experience in the cardiovascular literature suggest that nitric oxide-mediated

mechanisms are likely involved (Shen 1999).

Nitric oxide regulates many processes, including those related to vascular tone,

renal hemodynamics and alterations of the renin-angiotensin system. In short,

we don’t yet know the mechanism of hypertension in these patients. More

than likely, some component of all of these processes is involved.

At this time, we don’t have enough mechanistic information to drive the

selection of one antihypertensive medication over another. Currently, I suggest

making this decision based on other reasons one drug may be preferred versus

another — the way we do with all patients.

Tracks 4 and 6 Tracks 4 and 6

DR LOVE: Can you discuss the issues related to bowel perforation and

bevacizumab? What have we learned over the last year or two? DR LOVE: Can you discuss the issues related to bowel perforation and

bevacizumab? What have we learned over the last year or two? |

DR HURWITZ: The issues related to bowel perforation have many of the same

general themes as the arteriovascular event risks. In general, these risks are low.

Several studies of bevacizumab — the large IFL study (Hurwitz 2004), the

Phase II 5-FU/leucovorin study (Kabbinavar 2005) and the ECOG second-line

FOLFOX with or without bevacizumab study (Giantonio 2005) — have

reported a one to two percent risk of GI perforation. DR HURWITZ: The issues related to bowel perforation have many of the same

general themes as the arteriovascular event risks. In general, these risks are low.

Several studies of bevacizumab — the large IFL study (Hurwitz 2004), the

Phase II 5-FU/leucovorin study (Kabbinavar 2005) and the ECOG second-line

FOLFOX with or without bevacizumab study (Giantonio 2005) — have

reported a one to two percent risk of GI perforation.

A similar risk is apparent in the historic literature — anywhere between two

to five percent of some type of bowel perforation, abscess or fistula formation

with the use of chemotherapy alone.

The reasons for those findings are not well understood. These problems

have not been observed as commonly in other tumor settings, aside from the

ovarian cancer population. This may relate to the fact that GI-toxic regimens

are used for colon cancer — more diarrhea and bowel inflammation and inflammatory wound-healing responses, in general, may predispose these

patients to perforation.

DR LOVE: As bevacizumab data accumulate, have we learned anything more

about the clinical presentation of these bowel perforations? DR LOVE: As bevacizumab data accumulate, have we learned anything more

about the clinical presentation of these bowel perforations?

DR HURWITZ: For the most part, the presentation of bowel perforation is

what you would expect — essentially like an acute abdomen. The definition

of bowel perforation, though, has often been very liberal to allow us to detect

any event that might be even partially implicated. DR HURWITZ: For the most part, the presentation of bowel perforation is

what you would expect — essentially like an acute abdomen. The definition

of bowel perforation, though, has often been very liberal to allow us to detect

any event that might be even partially implicated.

As cancer doctors, we’re quite used to dealing with the complications of

regimens that affect bowel integrity. IFL, FOLFOX, and 5-FU alone all cause

diarrhea, and if that gets out of hand, it can lead to an occasional serious or

even life-threatening complication.

Patients who have bowel trouble and start to experience serious symptoms

should be evaluated urgently, and standard management should be pursued.

Tracks 8-9 Tracks 8-9

DR LOVE: What do we know about patients who require emergent

surgery while they’re receiving bevacizumab? DR LOVE: What do we know about patients who require emergent

surgery while they’re receiving bevacizumab? |

DR HURWITZ: The issue of surgery and bevacizumab needs to be broken

down into two separate categories. One category includes patients who have

major surgery and then receive bevacizumab. DR HURWITZ: The issue of surgery and bevacizumab needs to be broken

down into two separate categories. One category includes patients who have

major surgery and then receive bevacizumab.

Among patients who’ve waited at least a month prior to starting bevacizumab

and who have healed sufficiently to be cleared by their surgeons, no increased

risk of wound-healing complications is apparent. The converse setting, where

patients are on bevacizumab and then go to surgery, is a bit more complicated.

The best data come from the IFL study (Hurwitz 2004). Most of the patients

going to surgery did so for an urgent or emergent indication — usually major

abdominal procedures.

Wound-healing complications ranged from minor to major wound dehiscence

or major bruising at the site, and the wound-healing complication risk ranged

from about four to 14 percent.

Most complications were manageable — rarely lethal. I would interpret that

range in risk to mean that the rate does increase for emergent or urgent

indications, such as drainage of an abscess or some other acute issue. That risk

is acceptable, and the risk of wound-healing complications should not deter

good surgical or interventional management when needed.

For highly elective surgery, one should respect the half-life of the drug, which

is about 21 days. One should wait two to three half-lives of the drug — about

40 to 60 days — before elective surgery. This becomes a bit of a risk-benefit

ratio, as we have not truly identified the best interval for timing elective metastatic resection. I think the window for metastatic resections is probably

about six weeks following cessation of treatment with bevacizumab.

DR LOVE: With respect to hepatic resection or ablation, what do we know

about the effect of bevacizumab on hepatic regeneration? DR LOVE: With respect to hepatic resection or ablation, what do we know

about the effect of bevacizumab on hepatic regeneration?

DR HURWITZ: We don’t know a lot about the effect of bevacizumab per se

on hepatic regeneration. From clinical and preclinical information, we know

that hepatic regeneration is angiogenesis-dependent. DR HURWITZ: We don’t know a lot about the effect of bevacizumab per se

on hepatic regeneration. From clinical and preclinical information, we know

that hepatic regeneration is angiogenesis-dependent.

We also know that the majority of hepatic regeneration occurs within a few

weeks to a month or so after surgery. Some patients clearly take a little bit

longer to regain both liver volume and function after major resection, particularly

after a right hepatectomy.

In general, the patient should be well healed, should have normal liver

function test results, and should be cleared by his or her surgeon before

starting bevacizumab. I think a patient who’s completely healed and who has

normal liver function test results is a suitable candidate.

Allow two months, perhaps three months for some patients, to recuperate

from such surgery — that time frame would be reasonable. For the smaller

variations on hepatic resection, such as a left hepatectomy, shorter windows of

time may be appropriate.

The administration of bevacizumab after radiofrequency ablation has not been

well studied. It is a less invasive procedure, although it does have potential

risks. A window of two to four weeks after radiofrequency ablation is probably

adequate, provided the patient had no undue complications.

Track 16 Track 16

DR LOVE: Would you discuss the dosing of bevacizumab? DR LOVE: Would you discuss the dosing of bevacizumab? |

DR HURWITZ: In the first-line setting, a dose of 5 mg/kg every two weeks,

which is a dose intensity of 2.5 mg/kg per week, is the standard of care. Some

ongoing studies, mostly of capecitabine-based regimens with oxaliplatin, are

using three-week cycles of equivalent dose intensity. Those are 7.5 mg/kg

every three weeks, which is essentially the same dosing, particularly given the

long half-life of the drug. In the second-line setting, the dose is 10 mg/kg

every two weeks. DR HURWITZ: In the first-line setting, a dose of 5 mg/kg every two weeks,

which is a dose intensity of 2.5 mg/kg per week, is the standard of care. Some

ongoing studies, mostly of capecitabine-based regimens with oxaliplatin, are

using three-week cycles of equivalent dose intensity. Those are 7.5 mg/kg

every three weeks, which is essentially the same dosing, particularly given the

long half-life of the drug. In the second-line setting, the dose is 10 mg/kg

every two weeks.

An older study, the initial randomized Phase II trial (Kabbinavar 2003), evaluated

placebo versus 5 mg/kg versus 10 mg/kg. In that study, the

5 mg/kg dose was a little bit better. A number of disclaimers relate to potential

imbalances between the 5 and 10 mg groups. However, the 5 mg/kg dose

looked good enough to pursue in a Phase III study, and that dose is clearly

active. We know the safety profile of that drug in that setting.

Most patients have received bevacizumab in the first-line setting, so we see

very few reasons to give bevacizumab in the second-line setting. One can come up with a few scenarios, such as patients having been on a clinical trial

without bevacizumab or some complication that caused postponing the treatment.

If bevacizumab were truly to be used as a second-line agent, I would

use a 10 mg/kg dose. In a hybrid scenario, such as a delayed first-line setting, I

would use 5 mg/kg.

Track 17 Track 17

DR LOVE: What about the combination of cetuximab and bevacizumab

— where do you see that heading? DR LOVE: What about the combination of cetuximab and bevacizumab

— where do you see that heading? |

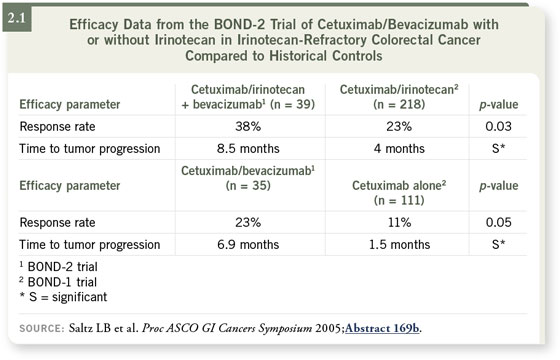

DR HURWITZ: The issue of combining biologics is an interesting one. Right

now, preclinical biology suggests synergy when targeting the EGF and VEGF

axes. Interesting pilot data came from the BOND-2 trial, which looked at

cetuximab with bevacizumab versus cetuximab/bevacizumab and irinotecan

(Saltz 2005). DR HURWITZ: The issue of combining biologics is an interesting one. Right

now, preclinical biology suggests synergy when targeting the EGF and VEGF

axes. Interesting pilot data came from the BOND-2 trial, which looked at

cetuximab with bevacizumab versus cetuximab/bevacizumab and irinotecan

(Saltz 2005).

Both arms of that study appeared to do much better than the historical

controls of the BOND-1 trial (Cunningham 2004), which evaluated cetuximab

monotherapy or cetuximab with irinotecan (2.1). The response rates and

time to progression were a lot higher than most of us expected.

For both theoretical and practical reasons, I think the combination is highly

worthy of study. Two studies will address this question. The largest study will

be a GI Intergroup study of one chemotherapy regimen picked by the investigator

— either FOLFOX or FOLFIRI — with the addition of cetuximab,

bevacizumab or both (CALGB-C80405). An industry-sponsored study will

evaluate FOLFOX/bevacizumab with or without panitumumab, a monoclonal

antibody that is essentially a biological cousin of cetuximab.

Track 20 Track 20

DR LOVE: Previously, you mentioned the issue of capecitabine with

bevacizumab. Is there any reason to believe this combination would be

better or worse than bevacizumab with 5-FU? DR LOVE: Previously, you mentioned the issue of capecitabine with

bevacizumab. Is there any reason to believe this combination would be

better or worse than bevacizumab with 5-FU? |

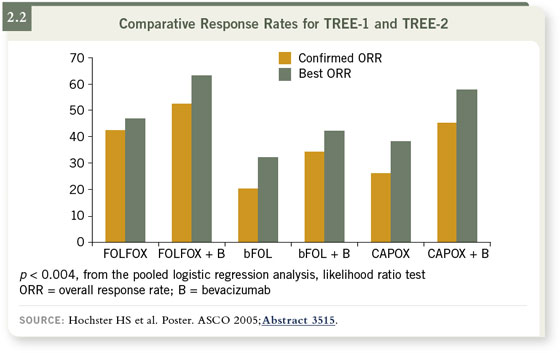

DR HURWITZ: My expectation is that the regimens would be comparable.

Large Phase III studies have been conducted, primarily in Europe, including a

FOLFOX versus CAPOX study with or without bevacizumab. This study has

completed accrual, and the toxicity results will be available in the next year.

Efficacy results will come shortly thereafter, but it may take a while for the

survival endpoint data to appear. DR HURWITZ: My expectation is that the regimens would be comparable.

Large Phase III studies have been conducted, primarily in Europe, including a

FOLFOX versus CAPOX study with or without bevacizumab. This study has

completed accrual, and the toxicity results will be available in the next year.

Efficacy results will come shortly thereafter, but it may take a while for the

survival endpoint data to appear.

In general, capecitabine has tended to look similar to 5-FU, including the

capecitabine/oxaliplatin versus infusional 5-FU/oxaliplatin data, without

bevacizumab, reported at ASCO this past year (Arkenau 2005; Sastre 2005).

In addition, pilot data from our institution and the larger experience in

the TREE-2 study suggest that efficacy should be comparable between

capecitabine/oxaliplatin/bevacizumab and the FOLFOX regimen (2.2). That

comparability, though, has not yet been validated. As far as clinical management

goes, I would still consider an infusional 5-FU regimen with oxaliplatin

or irinotecan — FOLFOX or FOLFIRI — as the standard platform on which

to add bevacizumab.

For patients who are not candidates for pump therapy, the activity of

capecitabine with oxaliplatin and bevacizumab is significant enough that it

should be considered as a first-line option. The question of whether or not it’s

the best option will require the final results of this Phase III study.

Select publications

|