| Tracks 1-17 |

| Track 1 |

Introduction |

| Track 2 |

Use of bevacizumab after discontinuation of chemotherapy or beyond disease progression |

| Track 3 |

Incorporation of panitumumab into clinical practice |

| Track 4 |

Infusion reactions with cetuximab versus panitumumab |

| Track 5 |

Treatment of potentially curable metastatic disease |

| Track 6 |

Management of synchronous primary and metastatic disease |

| Track 7 |

Patient acceptance of cetuximab-associated rash in trials of adjuvant therapy |

| Track 8 |

Capecitabine alone or with oxaliplatin for the treatment of Stage II disease |

| Track 9 |

Treatment of lower-risk breast and colon cancer |

|

| Track 10 |

Patient acceptance of adjuvant therapy for modest benefits |

| Track 11 |

Patient expectations about chemotherapy side effects |

| Track 12 |

A physician’s experience with a spouse being treated for breast cancer |

| Track 13 |

Impact of a personal experience with cancer on the practice of oncology |

| Track 14 |

Communication and children’s coping with a parent’s cancer |

| Track 15 |

The personal decision to participate in a clinical trial |

| Track 16 |

Impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment on lifestyle and relationships |

| Track 17 |

A personal perspective on the pace of progress in cancer research |

|

|

Select Excerpts from the Interview

Track 2

DR LOVE:

DR LOVE: What is your general approach to management of metastatic

colorectal cancer in clinical practice?

DR MARSHALL: I tend to follow an OPTIMOX-type strategy. Whether I’m

administering OPTIMIRI or OPTIMOX, I back off from irinotecan or oxaliplatin

after I see the optimum response, which is usually around four months

of therapy. Generally, I continue with 5-FU and bevacizumab.

DR MARSHALL: I tend to follow an OPTIMOX-type strategy. Whether I’m

administering OPTIMIRI or OPTIMOX, I back off from irinotecan or oxaliplatin

after I see the optimum response, which is usually around four months

of therapy. Generally, I continue with 5-FU and bevacizumab.

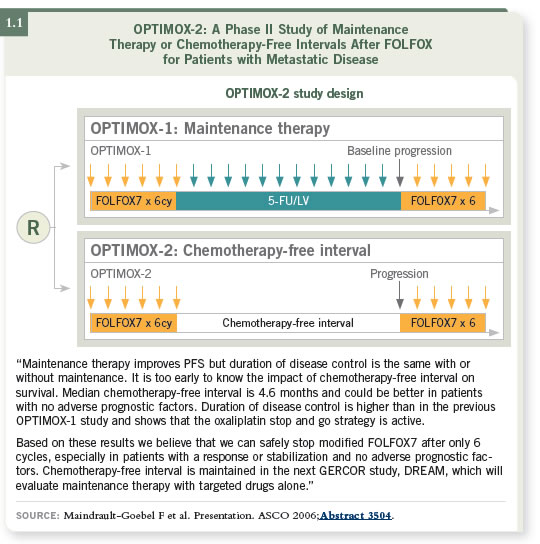

The recent OPTIMOX-2 data have given us permission to not administer

any agent during the chemotherapy-free window, so you could stop treatment altogether (Maindrault-Goebel 2006; [1.1]). However, as a clinical trialist, I

believe that may be the ideal opportunity to bring in new medicines.

We are beginning to design more trials to test new agents in the chemotherapy-free window to see if they are able to stabilize or prolong progression.

When patients reprogress on one regimen, I change to the other base chemotherapy.

However, many physicians like to resume the old chemotherapy:

If the patient was on oxaliplatin, they bring back the oxaliplatin, and if the

patient was on irinotecan, they bring back the irinotecan.

DR LOVE: When you switch regimens, do you continue the bevacizumab?

DR LOVE: When you switch regimens, do you continue the bevacizumab?

DR MARSHALL: At that point, I frequently bring in an EGFR blocker, even

though that has not yet been established by the data. More recent trials support

the practice of not waiting until the disease becomes irinotecan refractory

before bringing in an EGFR inhibitor. In fact, data for the EGFR inhibitors

now indicate that in almost every setting they’ve been tested in — last line,

second line, and now we have some first-line data — they’ve shown a positive

impact (Tabernero 2004).

DR MARSHALL: At that point, I frequently bring in an EGFR blocker, even

though that has not yet been established by the data. More recent trials support

the practice of not waiting until the disease becomes irinotecan refractory

before bringing in an EGFR inhibitor. In fact, data for the EGFR inhibitors

now indicate that in almost every setting they’ve been tested in — last line,

second line, and now we have some first-line data — they’ve shown a positive

impact (Tabernero 2004).

DR LOVE: When you make this decision with the patient whose disease is

progressing, do you factor in how they responded to the treatments?

DR LOVE: When you make this decision with the patient whose disease is

progressing, do you factor in how they responded to the treatments?

DR MARSHALL: Yes. If they progressed rapidly or didn’t respond well, I’m

less enthusiastic about keeping a drug on board, so I’ll switch it. But if they’ve

received a nice benefit from a drug, I don’t usually give that up.

DR MARSHALL: Yes. If they progressed rapidly or didn’t respond well, I’m

less enthusiastic about keeping a drug on board, so I’ll switch it. But if they’ve

received a nice benefit from a drug, I don’t usually give that up.

With bevacizumab, you can recognize a change in the biology of these tumors

— they slow down. It’s not necessarily that the tumors respond further, it’s just

that you have “turned them off,” so I hesitate to pull patients off of bevacizumab.

Clinically, that’s what we’re seeing — this quieting of colon cancer

and long-term survivors with metastatic disease.

Track 3

DR LOVE:

DR LOVE: Where does panitumumab currently fit into your treatment

algorithm?

DR MARSHALL: One of the most common questions I’m getting right now is,

“I’ve used cetuximab. Should I now administer panitumumab?” My answer

has been no.

DR MARSHALL: One of the most common questions I’m getting right now is,

“I’ve used cetuximab. Should I now administer panitumumab?” My answer

has been no.

However, I’m beginning to gain a little more experience with this patient

population, and I administer a lot of BOND-2, last-line regimens (Saltz 2005).

Recognizing that BOND-2 is with anti-EGFR or anti-VEGF treatment-naïve

patients, I will not let patients continue to progress without combining

EGF and VEGF inhibitors at some point. Clinically, when you put the two

antibodies together, you see fairly consistent activity, even in the nonnaïve and

the previously exposed patient.

I have been using cetuximab, and now I have patients who would like to take

the week off. They’re coming to me and saying, “Can I switch off and go to

panitumumab?” and I say, “Sure.” What’s interesting is that when I do so,

I see a little more renewed activity. I’m also seeing a renewed rash. A lot of

patients whose cetuximab rash quieted down are now receiving panitumumab.

Track 5

DR LOVE:

DR LOVE: Can you discuss your approach to potentially curable

metastatic disease?

DR MARSHALL: In general, I am increasingly adopting a chemotherapy-first

approach. In my opinion, patients who are going to benefit the most from

a surgical approach — a resection of the metastatic lesion — are those who

respond to chemotherapy (Delaunoit 2005).

DR MARSHALL: In general, I am increasingly adopting a chemotherapy-first

approach. In my opinion, patients who are going to benefit the most from

a surgical approach — a resection of the metastatic lesion — are those who

respond to chemotherapy (Delaunoit 2005).

The marker, if you will, of a responding metastatic lesion is encouraging and

powerful, so more and more patients are being offered surgery for oligo-metastatic

disease. We’re now having an opposite problem — a good problem.

I’m taking care of a young man right now who has a rectal tumor with two

liver metastases and is on a capecitabine trial.

After two rounds of CAPOX and bevacizumab, he has had such a good

response that we can barely see his two liver metastases, and his rectal lesion

has shown a nice response.

If I keep going too much more with chemotherapy, we’re not going to be able

to find the lesions to resect. Not that I think chemotherapy cured the patient,

but the lesions are now not detectable. What a good problem to have. Now we

have to dance that dance and make sure we don’t mismanage the rectal area

and that he still has a shot at a liver resection.

Our decision is that after four cycles we’re going to restage his cancer, then

pause and administer neoadjuvant radiation therapy, maintaining some

capecitabine and probably some oxaliplatin during that radiation therapy. We

will restage after that, and then most likely perform a rectal resection, and at

the same time, instead of a lobectomy, perform radiofrequency ablation on the

residual tumors.

DR LOVE: What is seen histologically in people who have clinical complete

responses in the liver?

DR LOVE: What is seen histologically in people who have clinical complete

responses in the liver?

DR MARSHALL: A lot of these people still have residual disease, but some

don’t.

DR MARSHALL: A lot of these people still have residual disease, but some

don’t.

DR LOVE: How do you decide whether or not to resect the area?

DR LOVE: How do you decide whether or not to resect the area?

DR MARSHALL: It’s a good question. For this particular patient, I called the

surgeon and asked, “What would you do if you got in there and you couldn’t

see it?” He knows anatomically where the lesions were, so he can resect the

region that they were in. It’s also important to note that even when traditional

imaging shows nothing, an ultrasound can find areas of disease. I was a

little nervous when this patient’s response was so good, thinking that we then

wouldn’t be able to perform what we hoped would be a curative resection on

his liver.

DR MARSHALL: It’s a good question. For this particular patient, I called the

surgeon and asked, “What would you do if you got in there and you couldn’t

see it?” He knows anatomically where the lesions were, so he can resect the

region that they were in. It’s also important to note that even when traditional

imaging shows nothing, an ultrasound can find areas of disease. I was a

little nervous when this patient’s response was so good, thinking that we then

wouldn’t be able to perform what we hoped would be a curative resection on

his liver.

Track 8

DR LOVE:

DR LOVE: What is your approach to Stage II disease?

DR MARSHALL: On one side, it’s clear that we’re dramatically overtreating

patients. We’re administering chemotherapy to 100 patients to help what may

be three to six people in the long run. I’m not fundamentally against that, but

I would like to figure out who may benefit and administer chemotherapy to

them. We are trying to recruit to a clinical trial (ECOG-E5202) that groups

patients according to the tumor’s genetic markers, and we’ve had some luck.

DR MARSHALL: On one side, it’s clear that we’re dramatically overtreating

patients. We’re administering chemotherapy to 100 patients to help what may

be three to six people in the long run. I’m not fundamentally against that, but

I would like to figure out who may benefit and administer chemotherapy to

them. We are trying to recruit to a clinical trial (ECOG-E5202) that groups

patients according to the tumor’s genetic markers, and we’ve had some luck.

For the most part, patients are interested in pursuing chemotherapy. Patients

with education — whether it’s fair education or not — will opt to receive

chemotherapy. My feeling is that community physicians are treating more of these people than they were before. They’re also using a lot more capecitabine

in this patient population.

DR LOVE: So for the patient at lower risk, some physicians are opting for

capecitabine alone because they “want to do something.”

DR LOVE: So for the patient at lower risk, some physicians are opting for

capecitabine alone because they “want to do something.”

DR MARSHALL: Yes, which doesn’t make sense to me. If you’re going to do

it, do it. The data say that FOLFOX would pick up a couple more people than

capecitabine by itself. I’ve heard Aimery de Gramont say this, and I agree with

him. If I were a Stage II patient, I’d rather receive three months of FOLFOX

than six months of capecitabine alone.

DR MARSHALL: Yes, which doesn’t make sense to me. If you’re going to do

it, do it. The data say that FOLFOX would pick up a couple more people than

capecitabine by itself. I’ve heard Aimery de Gramont say this, and I agree with

him. If I were a Stage II patient, I’d rather receive three months of FOLFOX

than six months of capecitabine alone.

DR LOVE: What about using capecitabine with oxaliplatin (CAPOX) in the

adjuvant setting?

DR LOVE: What about using capecitabine with oxaliplatin (CAPOX) in the

adjuvant setting?

DR MARSHALL: The metastatic data with capecitabine and oxaliplatin,

whether it’s infusion or bolus, are positive. So it is probably fine, and then I

put in my little asterisk and say, “But I’ve been wrong before.”

DR MARSHALL: The metastatic data with capecitabine and oxaliplatin,

whether it’s infusion or bolus, are positive. So it is probably fine, and then I

put in my little asterisk and say, “But I’ve been wrong before.”

Select Publications