| Tracks 1-16 |

| Track 1 |

Introduction |

| Track 2 |

Development of cetuximab and panitumumab |

| Track 3 |

Potential mechanisms of action of cetuximab and panitumumab |

| Track 4 |

Cetuximab-associated infusion reactions |

| Track 5 |

Relationship between infusion reactions and geographic variables |

| Track 6 |

Predictors of response to EGFR inhibitors |

| Track 7 |

Relationship between serum LDH and benefit from VEGF inhibitors |

| Track 8 |

Clinical management of metastatic colon cancer in the first-line setting |

|

| Track 9 |

Cetuximab-associated skin toxicity |

| Track 10 |

Clinical management of cetuximab-associated skin toxicity |

| Track 11 |

Considerations in evaluating bevacizumab and EGFR inhibitors in the adjuvant setting |

| Track 12 |

Assessment of EGFR |

| Track 13 |

Geographic variability in the side effects of fluoropyrimidines |

| Track 14 |

Relationship between folic acid and the side effects of fluoropyrimidines |

| Track 15 |

Mechanism of fluoropyrimidine toxicity |

| Track 16 |

Impact of diet and exercise on colorectal cancer |

|

|

Select Excerpts from the Interview

Track 3

DR LOVE:

DR LOVE: Can you discuss what we know about the mechanism of action

of cetuximab and panitumumab?

DR LENZ: These are two monoclonal antibodies that both inhibit the

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). The EGFR is a critical mainstay of

tumor development, tumor progression, metastasis and invasion.

DR LENZ: These are two monoclonal antibodies that both inhibit the

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). The EGFR is a critical mainstay of

tumor development, tumor progression, metastasis and invasion.

When you examine the data for either one of these two agents, you see

efficacy in the third- and fourth-line settings. This provides clues that the

EGFR is untouched by classical chemotherapy — there are no mechanisms of

cross resistance — and shows how important this receptor is in the process of

tumor progression.

We want to understand which patients might benefit most from these therapies.

The first goal is to evaluate the mechanism of resistance of cetuximab.

We went back to the literature and found data from animal models showing

that when tumors overexpress vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF),

cetuximab does not work.

In our clinical trial at the University of Southern California, 40 patients were

treated with cetuximab, again in the third- and fourth-line settings. When

we measured VEGF in the tumor, that’s exactly what we found: Tumors with

high levels of VEGF do not respond to cetuximab (Vallböhmer 2005).

DR LOVE: Is the VEGF receptor found on the tumor cells?

DR LOVE: Is the VEGF receptor found on the tumor cells?

DR LENZ: Yes. The VEGF receptor is expressed not only on the endothelial

cells but also significantly on tumor cells (Fan 2005). It is interesting because

with anti-VEGF treatment you have an anti-angiogenic effect as well as an

antitumor effect.

DR LENZ: Yes. The VEGF receptor is expressed not only on the endothelial

cells but also significantly on tumor cells (Fan 2005). It is interesting because

with anti-VEGF treatment you have an anti-angiogenic effect as well as an

antitumor effect.

Track 8

DR LOVE:

DR LOVE: In general, how do you approach first-line therapy in

metastatic colon cancer?

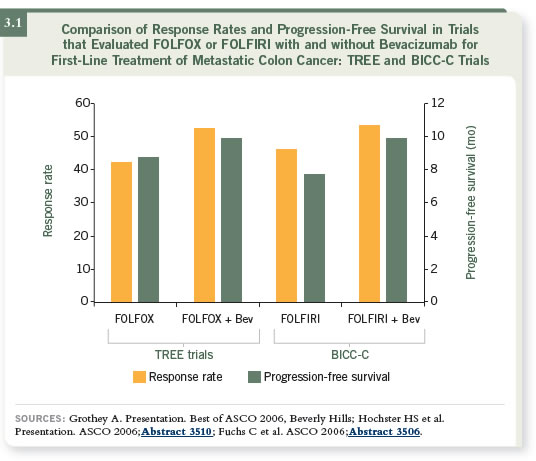

DR LENZ: I usually use either a backbone of FOLFOX or FOLFIRI, usually

combined with bevacizumab. We know some patients will benefit more

from FOLFIRI and others will benefit more from FOLFOX, and that will

also be true for bevacizumab and cetuximab (3.1). We know that bevacizumab

has little activity as monotherapy. It needs chemotherapy to be effective

cytotoxically.

DR LENZ: I usually use either a backbone of FOLFOX or FOLFIRI, usually

combined with bevacizumab. We know some patients will benefit more

from FOLFIRI and others will benefit more from FOLFOX, and that will

also be true for bevacizumab and cetuximab (3.1). We know that bevacizumab

has little activity as monotherapy. It needs chemotherapy to be effective

cytotoxically.

Track 14

DR LOVE:

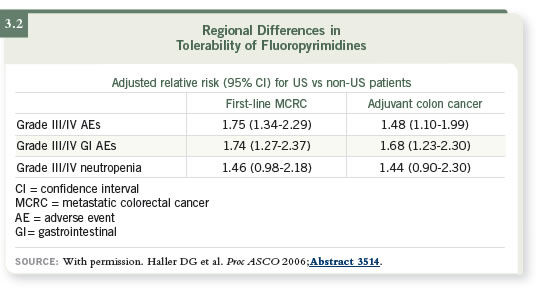

DR LOVE: What did you think about the presentation done at ASCO

2006 evaluating the side effects of fluoropyrimidine monotherapy based

on geography (3.2)?

DR LENZ: Dan Haller presented these data, and he comprehensively evaluated

the frequency of side effects of 5-FU or capecitabine in the United States

and the rest of the world (Haller 2006).

DR LENZ: Dan Haller presented these data, and he comprehensively evaluated

the frequency of side effects of 5-FU or capecitabine in the United States

and the rest of the world (Haller 2006).

An ongoing discrepancy exists between the toxicities reported in Europe and

the United States, and we know there are significant differences in 5-FU

toxicity among different ethnic populations. Asians, African-Americans and

Caucasians experience different levels of toxicity. That is explained by the

genetic make-up of the patient — not the tumor.

The biggest difference between Europe and the United States is the supplementation

of food with folates, which has a significant benefit for cardiovascular

and neurological development and so on. In Europe, folate supplementation

is not common. We also know that Americans are much more eager to

supplement their diet with vitamins, including folic acid.

We believe one of the major explanations for the differences in f luoropyrimidine

toxicities may be the supplement of folate in our food and the intake of vitamin

supplements. The more supplementation of folate, the higher the toxicity.

We also believe another reason may be some difference of genetic background,

because our populations have changed and the genetic pool is not as homogeneous

as when the immigrants came over from Europe.

However, I don’t believe that’s the only explanation. I believe there is a

lifestyle factor in that equation. From my point of view, the most reasonable

explanation for the differences in toxicities by region is a combination of

genetic background and folate supplementation, and that’s exactly what Dan

Haller concluded.

Select Publications